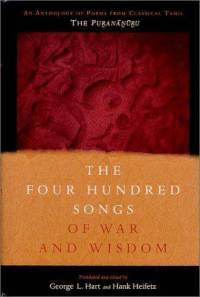

The Four Hundred Songs of War and Wisdom: An Anthology of Poems from Classical Tamil, the Purananuru

George L. (tr.) Hart and Hank Heifetz (tr.)

Hart, George L. (tr.); Hank Heifetz (tr.);

The Four Hundred Songs of War and Wisdom: An Anthology of Poems from Classical Tamil, the Purananuru

Columbia University Press, 2002, 320 pages

ISBN 0231115636, 9780231115636

topics: | poetry | tamil | india-ancient | translation

review

Purananuru is an anthology of old Tamil poetry, the oldest of the eight Sangam anthologies. Literally, the title means four hundred puRam songs - i.e. songs of the exterior - largely praising warriors, war, and also elegies to the dead. The four hundred poems are composed by more than 150 poets dating from between the first and third centuries C.E.. Written in old Tamil, this literary anthology had already been stabilized by the 3d c. CE, before Aryan influence had penetrated the south. It forms part of the extensive Sangam Literature (poetry) dating from 300BC to 300AD.

puRam poetry: seven tinais

What is interesting is that by the 1st c. CE, around when most of these poems were composed, there was already a flourishing literary tradition with entrenched conventionalized categories, which were listed in the tolkAppiyam, composeed around 2nd c. CE. At the highest level, short poetry forms could be in akam and puRam (interior and exterior) categories. Each class had its entrenched forms; thus akam dealt with themes of love and were in the form of a monologue to a lover or a friend; puRam poetry was often about war and addressed a real king. Within each class there were several modalities; thus the analysis of the poetic moods in puRam poetry is classified into seven moods or tinai (lit. place, but in this context, more of a mood, also called punn, tamil for rAga). These seven are listed in the tolkAppiyam as:

1. veTci : prelude to war, cattle raid; [akam counterpart: kuRiNci: night, on a mountain] 2. vāNchi : preparation for war, start of invasion, and recovery of cattle. [akam counterpart: mullai; rainy season, meadowland] 3. uLiNai : siege; defense of fort [akam counterpart: marutam] 4. thumpai pitched battle, [akam counterpart: neytal]. evening, grief 5. vākai : victory. [akam_ pAlai] 6. kānchi : transience of the world 7. Pātān : praise of kings, elegy, asking for gifts

Even the metaphors had conventionalized schemes of signification. Of course, the analysis developed over the centuries, and by the time the anthologies of sangam literature were compiled (c. 8th century), there were more elaborate forms. But what is striking to the modern reader is that, as in China, by the first centuries CE, not only had these large body of poems been composed, but there was a poetic sensibility refined enough to order these into genres of akam and puRam and then these many tenai or mood categories. Clearly this is the tip of a much older oral tradition that persisted for many centuries in Tamil verse. Further, a large number of the Sangam poems were translated later into Sanskrit and may have also influenced tropes in classical sanskrit poetry.

War and drinking

In terms of content, it is interesting to note the extent to which the poems are soaked through with toddy. The warrior king is forever indulging in his favourite toddy, made from palm, mohua flowers and other fruits. It is regularly drunk before battles (poem #292) and to fight off "shivers and chills" (#304). Strong liquor is clearly more heroic ("aged toddy strong as the sting of a scorpion", #392). After drink, the warrior-king becomes more generous with his gifts (123), and a shared drink is a sign of bonding (290), etc. A couple of poems mention wine, which was brought to them by the yavanas (greeks). Almost one in four poems has one of the words "toddy", or "liquor".

Anyone visiting these regions in Kerala and Tamil Nadu will not fail to note the continuing importance of palm toddy or "kallu" in these areas.customers at a kallu shop overlooking the scenic tea-estates of chinnakanal in the nilgiris above munnar, kerala

The translations

This translation is a work of collaboration between Tamil scholar George Hart and poet Hank Heifetz. Many of these poems had earlier appeared in translations by George Hart. One noticeable difference is that in the earlier versions, Hart had kept a meter and scansion in his lines; the translations now are mostly prose. Personally, I seem to like some of those earlier versions, though some versions have clearly improved. as an example, consider the opening lines of poem 38. in Hart's earlier version: Victorious king on a young mountainous elephant, whose great army has waving flags of many colors that seem to wipe the sky! in Heifetz's rendering: Victorious king, you who ride a mountain of an elephant and lead a vast army with flags of many colors that flutter as if they were brushing the sky clean. We see that the infelicity of "mountainous elephant" has been replaced, and "brushing the sky clean" is clearer than "wipe the sky". At the same time, I feel the new version often tends to verbosity - and brevity must lie at the heart of any poetic enterprise. Thus, it is not clear to me on the whole these are real improvements. In the above, for instance, if we take Hart's original version and change to "mountain-like" and "wipe the sky clean", and replace "has waving" with "waves" - then we would have remained compact while reflecting the meaning adequately, without the additional burden of so many words. Also, the scansion of Hart's originals give a better sense of the poetry, even in translation, than the pure prose versions. On the whole though, most poems in the translation read quite well in English, but they tend to verbosity quite often. They are presumably all quite faithful to the originals. But read as English poetry, the translations by Ramanujan often fare better (see 102 below), and also some of the versions by Vaidehi. A key shortcoming in the volume is the absence of an index of first lines. The main index attempts to capture enough hints for the main theme words, but it is far from a concordance and it remains difficult to find a particular poem. Also, why the index lists the page numbers and not poems is unclear; as in Ramanujan's Poems of Love and War, surely a notation such as 137, [137] could have indicated the poem number and its notes. - amitabha mukerjee nov 2012

Excerpts

Auvaiyar : Purananuru #91

Kings in the line of Atiyans! You who pour out the toddy that makes men roar! You whose powerful hand with its sliding bracelets triumphs and brandishes an infallible sword that brings you victory, cutting your enemies down on the field! Anci of the golden garland, rich in murderous battle! May you live as long as he lives on whose head the crescent moon glows, whose neck is as a dark blue as sapphires! Oh greatness! Without considering how difficult it is to obtain the sweet fruit Of Nelli plant with its tiny leaves , which has to be plucked from a crevice on the summit of an ancient mountain hard to climb, you kept silence in your heart about it powers, and so that you might rescue me form death, you gave that fruit !

Auvaiyar: The spare axle #102

p.71 Those who sell salt carry a spare axle with them lashed to the wood underneath because they think about oxen who are young and unacquainted with the yoke, about a heavy load in the wagon which must pass over heights and travel low ground and who knows what may happen? You, so bright with glory are like that axle, your hand a cup for giving to others! Greatness! You are like the moon at the time when it is full! How can there be darkness for those living under its radiance. [Auvaiyar is the most prolific of the dozen or so women poets among the composers of these poems. Her work also appears in several other anthologies]

Alternate translation by AK Ramanujan: A Young Chieftain

The young bull does not feel the yoke, though the cart is loaded with salt and things. But who can foresee the damages when it dips into creeks and climbs the hills? So the salt merchants keep a second safety axle under the axletree. You are such, lofty one with bright umbrellas of fame: whoever lives in your shade, living as under the fullest moon, has any fear of night? [Auvaiyar: on Pokuttelini] Purananuru 102 (from Poems of Love and War p.141)

Kapilar for King Pari #107

p. 73 "Pari! Pari!" they say, and with their eloquent tongues the bards praise one man and sing of his many strengths. But more than only Pari matters. The monsoons too are here to preserve the world! [earlier version by Hart: Again and again they call out his name "Pari! Pari!" Thus do poets with skilled tongues all praise one man Yet Pari is not alone: there is also the rain to nourish this earth. ] kapilar appears to have been the court poet for a Vel Pari king, in the Nilgiri region (around Coimbatore / Erode), c. 3d c. CE. When Vel Pari is killed in battle, kapilar is supposed to have committed suicide by vadakirrutal - facing North and starving.

Kapilar for King Pari #118

That small reservoir with its clear water and its sloping shore like a half moon running along hills and knolls now is shattered in the land that was once governed from cool Parampu by PAri who gave chariots away and whose massive arm held a sharp spear.

Kapilar: giving away chariots #123

if someone takes his seat every morning in his court and drinks himself blissfully drunk,its a simple thing- then, to give away chariots! but Malaiyan whose good name glows and is never diminished,even without getting delightfully drunk, gives away more lofty ornamented chariots, than the drops of rain that fall on the fertile Mullur mountain!

version by Ramanujan #123

If a man's drunk from morning on and delighted with the crowd in the court, it's easy for him to give away a chariot or two. But the tall gold-covered chariots given by Malaiyan of everlasting fame, given when he's sober, outnumber the raindrops on the rich peaks of Mullur. (Poems of Love and War, p. 153)

ParaNar to king Pekan #142

p. 90 Like the clouds who form part of an endless family raining down on the dry reservoirs, on the wide fields, even on arid salt flats rather than where they might be useful, with his elephants in rut, war anklets on his feet, this is Pekan! Ignorant though he is of how to grant gifts, marching against an enemy army no ignorance marches with him! original old tAmil: அறுகுளத்து உகுத்தும், அகல்வயல் பொழிந்தும், உறுமிடத்து உதவாது உவர்நிலம் ஊட்டியும், வரையா மரபின் மாரி போலக், கடாஅ யானைக் கழற்கால் பேகன் கொடைமடம் படுதல் அல்லது, படைமடம் படான் பிறர் படைமயக் குறினே.

paraNar on Pekan's abandoned wife kaNNaki #144

p. 91 How can you be so coldly cruel, so without compassion? As we were playing our small yAls in the cevvaLi rAga of longing and singing of your forest, the look of it during the monsoon! we saw a young woman in grief that seemed to have no end, her darkened eyes glowing like dusky, fragrant waterlilies but overflowing with tears that fell to wet her breasts adorned with their ornamentation. Bowing down to her, we asked of her, "Young woman! Are you some relation to the lord who wants us to be with him?" With her fingers like budding red kAntaL flowers she brushed away her tears and then said to us, "I am no relation of his! Hear me out! Pekan, whose fame glows, hungers for the beauty, they say, of another woman who resembles me and in his resounding chariot he pays his frequent visits to the lovely city that is all encircled with jasmine!" [there are 5 poems 143-147 appealing to king Pekan on behalf of the abandoned kaNNaki. These poems are classified in the puRanANURu in the tinai peurntinai, a mood that does not appear in the tolkAppiyam.] அருளா யாகலோ கொடிதே; இருள்வரச், சீறியாழ் செவ்வழி பண்ணி யாழ நின் கார்எதிர் கானம் பாடினே மாக, நீல்நறு நெய்தலிற் பொலிந்த உண்கண் கலுழ்ந்து, வார் அரிப் பனி பூண்அகம் நனைப்ப, இனைதல் ஆனா ளாக, ‘இளையோய்! கிளையை மன், எம் கேள்வெய் யோற்கு?’என, யாம்தன் தொழுதனம் வினவக், காந்தள் முகைபுரை விரலின் கண்ணீர் துடையா, ‘யாம், அவன் கிளைஞரேம் அல்லேம்; கேள்,இனி; எம்போல் ஒருத்தி நலன்நயந்து, என்றும், வரூஉம் என்ப; வயங்கு புகழ்ப் பேகன் ஒல்லென ஒலிக்கும் தேரொடு, முல்லை வேலி, நல்லூ ரானே!’ (original tamil)

konaTTu ericcilUr mAtalaN maturaik kumaranAr #180

(about his patron, irntUr kiLAN tOyaN mAraN) He doesn’t have the wealth that everyday he would lavish on others Nor the pettiness to say that he has nothing and so refuse! Enduring the troubles that have fallen upon him as king, cured of his suffering from those noble wounds endured when weapons on the field of battle tasted his flesh, the handsome scars have grown together as if he were a tree with its bark striped for use in curing and his body is perfect! Not a scar! In Irntai he lives and practices generosity! He is an enemy to the hunger of bards! If you wish to cure your poverty, come along with me, bard whose lips are so skilled! If we make our request of him, showing our ribs thin with hunger, he will go to the blacksmith of his city and will say to that man of powerful hands, "Shape me a long spear for war, one that has a straight blade!"

Auvaiyar: Whether you grow rice

#187 p. 120 Whether you grow rice or whether you are a forest, whether you are a valley or whether you are a mountain, if they are good men who inhabit you, then you are good, land! and may you long flourish!

alt tr. by Ramanujan: Earth's bounty

Bless you, earth,

field,

forest,

valley,

or hill,

you are only as good

as the good young men

in each place.

(from Poems of Love and War p.159)

karuvUrp peruN catukkattup to koperuncolaN who is fasting to death #219

[the cycle of poems from 213 to 223 mourn the event when the early chola king Kopperuncholan faced a revolt by his two sons. Rather than fight and kill them and leave the country without heir, he is advised by his poet-friend to kill himself in the Tamil tradition of vadakiruttal, where one faces north and fasts till death. A number of his companions also fasted with him. in this poem, karuvUrp appears to be lamenting the fact that the king has not invited him to fast alongside.] Warrior! You who are wasting away all the flesh on your body under the speckled shade, on this island in the river! Are you angry with me? For those summoned by you who have sat down beside you are many!

Earlier version by George Hart

On an island in a river, in a spotted shade, you sit and your body dries up. Are you angry with me, warrior who have asked so many to join you here? —The song of KaruvÚrp Peruñcatukkattup PÚtanataùÁr to king Kõperuñcõãaù as he faced north [to starve himself to death].

kuTTuvaN kIraNAr : death of a king #240

p.149 He who gave away horses with gaits of various rhythms and elephants and whole territories and cities and unending revenue ceaselessly to singers, Ay aNTiraN has gone to the world of the gods accompanied by his women with their tiny bangles and their high-sloping mounds of love, when Death who has no mercy took them away. At the side of a burning ground where sedge grows, where a wide-mouthed owl settled into the space of the hollow of a tree hoots to the dead his message that they must burn and be added to the ashes, his body rested, and vanished as the glowing fire consumed it. The eyes of poets have been dimmed. Nowhere do they see anymore who can shelter them. Their families clamor but they can do nothing for them and they go off shrunken with hunger now, away to the countries of other kings! ["mounds of love" - அல்குல், alkul = pubic area]

Auvaiyar: Give him liquor and then drink yours

Puranuru 290, p.171 Give him liquor and then drink yours! O lord of raging war and of herds of elephants and of handsome chariots! The father of your father and the father of his father together--- like the hub set by a carpenter at the center of a wheel--- stood their ground on the field where men raise and hurl spears and there, without blinking, perished. He too is a man of might, famed for his courage. Like a palm-leaf umbrella when it is raining, lord! he will ward off the spears they aim at you. links: * http://learnsangamtamil.com/purananuru/ (Tamil w English translations, mostly by Vaidehi, and a few by Hart * http://puram1to69.blogspot.in/ (in Tamil) * lankanewspapers English only with brief explanations * project madurai tamil eTextObv: Bust of king. Prakrit legend in the Brahmi script: "Siri Satakanisa Rano ... Vasithiputasa": "King Vashishtiputra Sri Satakarni" Rev: Tamil Brahmi script: "Arah(s)anaku Vah(s)itti makanaku Tiru H(S)atakani ko" - which means "The ruler, Vasitti's son, Highness Satakani" source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Satavahana_Bilingual_Coin.jpg

bookexcerptise is maintained by a small group of editors. get in touch with us! bookexcerptise [at] gmail [dot] .com. This review by Amit Mukerjee was last updated on : 2015 Mar 31